23rd and Union

A Scramble for the CD

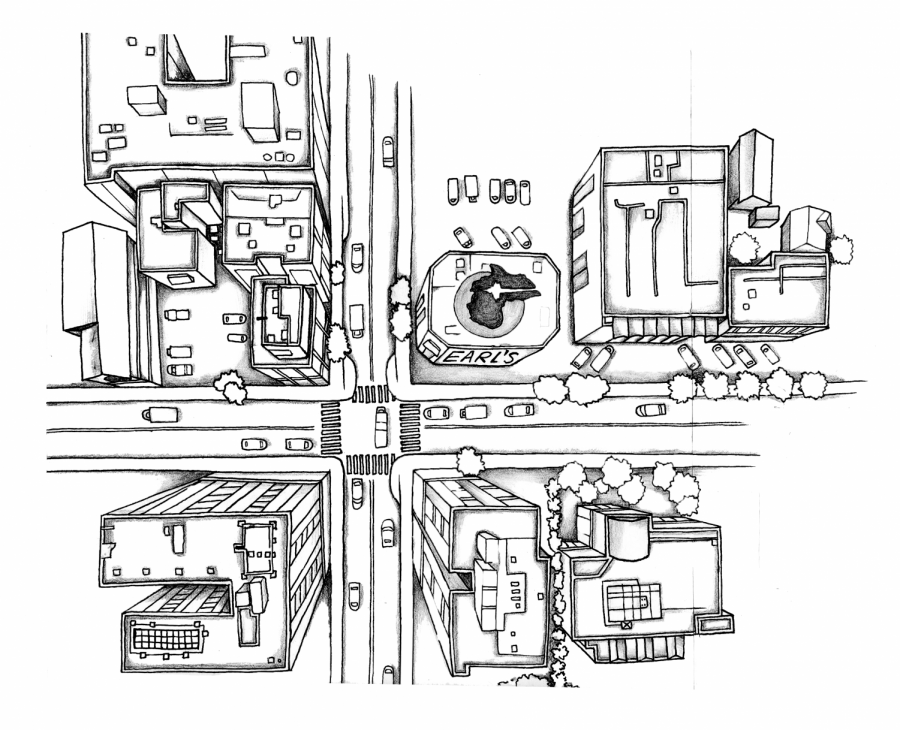

23rd and Union is a corner with some of the richest and most deeply-rooted history in Seattle. But things are changing. Everybody is scrambling for a spot in the Central District. Whether it’s developers, 30-year locals, or people searching for new apartments, pieces of the CD are being snatched up by the second.

“Developers came with a narrative that Black people didn’t want to be in the CD. So it’s very important for us, as an organization [Africatown], to let developers and government stakeholders know that Black people want to be here and many of us have never left,” said Omari Salisbury, a marketing and communications officer for Africatown. “And the Black people that have have had to leave, majority have been forced out.”

Gentrification and constant change is something that the Black Seattle community has become all too familiar with.

“We have to learn to have no emotion,” said Jason Moore, a barber from Earl’s Cuts and Styles. This has led many locals to hold pessimistic ideas and hopeless views.

“We are holding on to what’s already gone,” Moore said.

Efforts are already being made to soften the blow of gentrification on the community by creating a space to remember the history of the CD before the change. The Africatown Community Land Trust has plans to create a building made for the Black community, which was, and still is, being pushed out of the Central District. This building will be named the Liberty Bank in honor of the history of the area.

“On 23rd and Union there was the very first Black owned bank West of the Mississippi river,” said Salisbury.

This building will not only have affordable housing but a Seattle soul food restaurant named “That Brown Girl Cooks!” with the local barber shop “Earl’s Cuts and Styles” underneath.

Africatown is an attempt to preserve the history that has been part of the CD for 140 years and is now being erased.

“In the Central District, people want to just steamroll over our history, [they] act like we were never here,” Salisbury said.

Systematic attempts to move African Americans out of the Central District have been around for decades, and the effects can be seen today.

“The gentrification in the Central District has been systemic.” Salisbury said.

Salisbury was a Garfield student around the time of project Weed and Seed, a government program to reduce crime, drug abuse and gang activity in high crime neighborhoods.

This program targeted poor Black neighborhoods tried to “lower crime” by forcing people out of their houses for possessing illegal substances. While project Weed and Seed has ended, some may think that this gentrification is simply a more modern version.

Africatown has played a large role in giving a voice to the community when it was forcefully silenced. The organization has met with South Lake Union Apartments, owner of a majority of the apartment buildings on 23rd and Union and many more, to create the Liberty Bank building and hold events for the community and the culture.

While Africatown is largely supported by many, other members of the community feel they are not proportionally represented.

Saad Ali, the owner of the 99 Cents Corner store on the 23rd and Union lot, has expressed serious frustration and concern regarding the changes. Lake Union Partners, Capitol Housing, and Africatown itself are awaiting his departure.

“They kept texting, calling, sending letters, telling me to move out,” Ali said.

He then received 400 signatures for a petition to stay at his location.

“I was supposed to move out on December 31st. I’m still here. I told them I’m not moving,” Ali said.

“I needed $50,000 to relocate, find another place, and keep working,” Ali said. At first, Ali was not offered any relocation money which led to fear regarding his future.

As an immigrant business owner and someone who has been on the lot for over 20 years, the offers he was receiving were simply not enough. After various meetings and prolonged back and forth, Capitol Hill Housing and Africatown offered Ali aid during his search for a new location.

“This city has changed a lot. They started pushing people out years ago and slowly but surely it has completely changed,” Ali said.

He explained that 90% of his customers have moved away from the Central District into the suburbs and outskirts of Seattle.

As rent costs reach skyrocketing numbers, low-income and minority populations are often targeted, which forces a suburban sprawl. With the people goes the culture, community and history. Ali’s 99 Cents is one of the few corner stores left in the CD.

“Once I close this store, you won’t see nobody,” Ali said. The Central District community has been spreading farther and farther apart as families search for affordable housing anywhere possible.

Ali is now searching for a new location and getting ready to leave.

As old community members say their goodbyes, others are being welcomed with open arms. Two large apartment buildings have opened across from Uncle Ike’s and Earls Cuts and styles. East Union apartments opened in November, replacing the old 76 gas station. With 85% of the building already filled, resident numbers only continue to grow. Most apartments are one bedroom and one bath with an average rent of $2,000.

A spacey gym, a beautiful large rooftop, and a Tacos Chukis right across the street, make the apartments undeniably sought after. However, the building will also house a New Seasons, a Portland-based grocery store with a controversial history of low wages and poor working conditions.

With high rent come those who can afford it. Residents are mainly upper-middle class, and a majority are white, coming -from similar occupations.

As new and old residents co-exist, there has been a clash in cultures.

“Us people who have been here for a while feel alienated,” said local Ted Evans, who feels that people who are from the CD originally are looked down upon.

Passersby who know the history of the neighborhood spoke of the changes, saying “it’s a slap in the face” and “this is what colonialism looks like.” While newcomers feel that “you have everything you need here”, “it’s changed, I guess, for the better.”

In attempts to tackle this issue, buildings have made some accommodations, “the NFTE [Network for Teaching Entrepreneurship] forces 20% of the building to be affordable housing,” said Everline Animas, Assistant Community Manager of the building. The Liberty Bank Building itself will be solely for affordable housing in attempts to cater to low-income families.

The Central District is our neighborhood, and as Bulldogs we must continue our legacy of fighting for what we believe is right. The history of the CD is the history of Garfield High, and as the CD changes, so are we.

“The biggest threat for Garfield with gentrification is losing our magic forever. If people value what makes Garfield special, that is what makes you want to get involved,” Salisbury said.

To get involved with what Africatown is fighting for, text “HOME” to (206) 309-6324. It allows Africatown to know who is willing to assist in meetings, organizations, take part in protests and so much more.

“Do something. Do something and believe in it.” Salisbury said. “Garfield is more than just a high school that you know. It’s a legacy. It’s a place that’s so magical.”

Izzy Lamola is a senior writer on The Garfield Messenger. They love InDesign, despite the tedious work, and is a lover of opinion pieces and op-eds. They...