Open to Expression

Exploring Seattle’s unique drag scene.

Drag spent decades relegated to the underground, but in our post-RuPaul and more queer-friendly world, drag has hit the mainstream. The side effect? Losing touch with the culture that makes Seattle’s drag scene unique.

“The performers that ended up on RuPaul’s Drag Race from Seattle are all very traditional, when in reality Seattle’s drag scene is more artistic and rooted in counterculture,” said Brendan Mack, a local queen and playwright who performs as Butch Alice.

“Seattle doesn’t give a flying f*** about mainstream,” Mack added. “Queens are doing their own art and they aren’t trying to imitate other people.”

Mack’s art is playwriting: in original works like The Fog Machine Play (written to justify a 2013 purchase of a fog machine) Mack aims to create an experience “where you don’t know what [the play will be like but] you know you have to be there.” Drag’s sprinkled in for fun rather than any particular reason.

“The coolest part of drag is that you can slap it onto anything,” said Strawberry Shartcake, another local queen and 2017 winner of the Miss Bacon Strip drag pageant.

“There’s so much drag you can see in Seattle: the more stereotypical pageant, ‘beauty parlor’ drag, or the queer genderfluid drag,” said Rainbow Gorecake, one of Seattle’s youngest professional queens.

Genderfluid drag is part of what makes Seattle’s scene stand out. Neither Strawberry Shartcake nor Butch Alice present in a traditionally “feminine” way like RuPaul’s queens; Strawberry sports a magnificent mustache and Alice bares her beard proudly. This kind of drag is called “genderf***.” The purpose of genderf*** is to transgress traditional notions of “masculinity” and “femininity” and open spaces for alternative expression.

“Drag queens are always at the forefront of queer change” said Issa Man, a local Alaska-raised queen.

Visage “Legs” Larue challenges the relationship between sex assigned at birth and drag. “A lot of times people think I’m a man, or I’m trans, but I’m assigned female at birth and I’m a drag queen.”

Larue deploys drag to explore hyperfemininity. “[Drag]’s an artform that’s over the top, it’s taking things to the extreme,” Larue said.

Strawberry employs hyperexpression to challenge norms about gender and sexuality. Through drag, Strawberry expresses queer hypermasculinity to create a space where people feel comfortable with nonconformity in artistic expression and public spaces. That expression can involve crossdressing, heels, and mascara; it can involve mustaches, beards, and lashes; or it can involve something else entirely.

“[People have preconceptions] like ‘if you’re not wearing nails you’re not doing drag’ or ‘if you’re not wearing lashes you’re not doing drag,’” Larue said. “[Yet] if people were to take a step back and look at it as an art form they could see we don’t compare Picasso to Michaelangelo. They’re two totally different styles but they both created beautiful pieces.”

Spaces where people express gender and sexuality in nonnormative ways help queer people feel like they have a community and a home, especially when they don’t have a home otherwise. “I felt like I had finally found my place,” Larue said.

Seattle’s scene also stands out for its inclusivity. “Seattle is a safe space because people are brave here — there are people saying ‘you know what, we’re just going to go out and be ourselves and dress [how] we want, we don’t care’,” Issa said.

All the queens we talked with shared the same sentiment: a community that celebrates you, no matter your gender or sexuality, has played an important role in their lives. Strawberry thinks that one of the exciting parts about being a queen is being a leader in that community – a “matriarch.”

Mack divides queens into three categories. First, there are the kind-hearted queens that will take thirty minutes to sit in the corner with a complete stranger and be their ally whether they’re going through a breakup, an identity crisis, or just having a rough day. They’ll say all the right things to make that person feel great.

Then there are the spokesperson queens. “Not every [queer] person is super extroverted,” Mack said. “Sometimes they need someone to get on stage, in a costume and wig, and say things because someone else in the community can’t.” These queens hone in on important issues like safe sex, allyship, and support for art in gentrifying communities.

Finally, there are the activist queens who put their voice behind politicians, charities, and social issues. “Any mayoral campaign in Seattle has a bunch of different drag queens that are behind them and supporting them,” Mack said.

“As drag queens we have platforms. People come see us perform and they know our names; they listen to us. When people listen to you, you have a platform and with platforms come change,” Issa said.

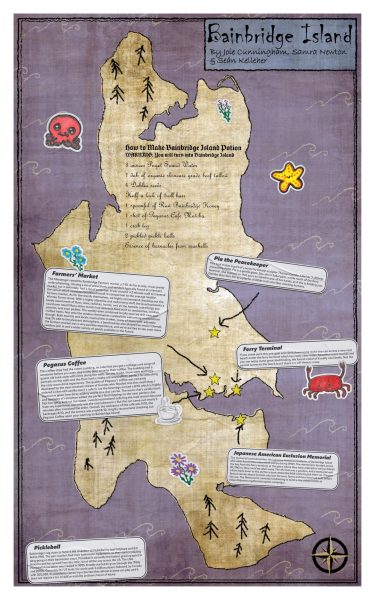

That platform has grew as drag has branched out to new spaces not traditionally associated with drag. “Lately, the coolest thing I’ve been noticing is a lot of straight-oriented bars are hiring [queens] – almost as ‘douche-repellent,’” Strawberry said. Larue noted that queens are performing at all kinds of new spaces, like a beer shop in Greenwood.

Although drag has become accessible to more audiences, age remains a barrier. Some venues, like Copious, host all-ages shows, but spaces like these are rare. During the two-week process of interviewing local queens for this article there were no all-ages shows to attend. The age restriction makes sense for some shows, like “draglesque” (a portmanteau of “drag” and “burlesque”), but age restrictions bar young people from family-friendly drag because (pun intended), most drag is at bars.

As drag goes mainstream it faces the same challenge as Grunge did in the nineties: pulling in enough cash that queens can pay their bills without sacrificing drag’s counter-culture integrity and, as Strawberry put it, “turning it into a big gross capitalist corporate nightmare.”

How can drag balance artistic integrity and paying the bills? All the queens said the same thing: stop the competition between bars.

“There’s a lot of fighting between the [bars] – not the queens – but it’s still affecting where they get booked,” Strawberry said. “A lot of venues tell performers that they can’t perform at other places, because you can imagine, if I belonged to a specific show and I got booked in a different show on the same night, [then] there’s a bunch of followers leaving the show I’m usually in to come see something else,” Mack explained.

Fights between bars hurt the community. Casts have become so solified that there’s little crosspollination between different styles, and queens get blamed for issues that have nothing to do with them. These fights run counter to everything Seattle’s drag community stands for: inclusivity, allyship, and nonnormativity.

“I would really love it if there was more crossing between the venues and the styles of drag […] casts get pretty solid for most of the main shows […] but opening up doors for more drag kings and female drag artists like myself [would be great],” Larue said.

“I want there to be more venues for us to perform at. I think drag should be everywhere. I want twice as much drag as we already have because it’s such an integral part of the queer community,” Issa said.