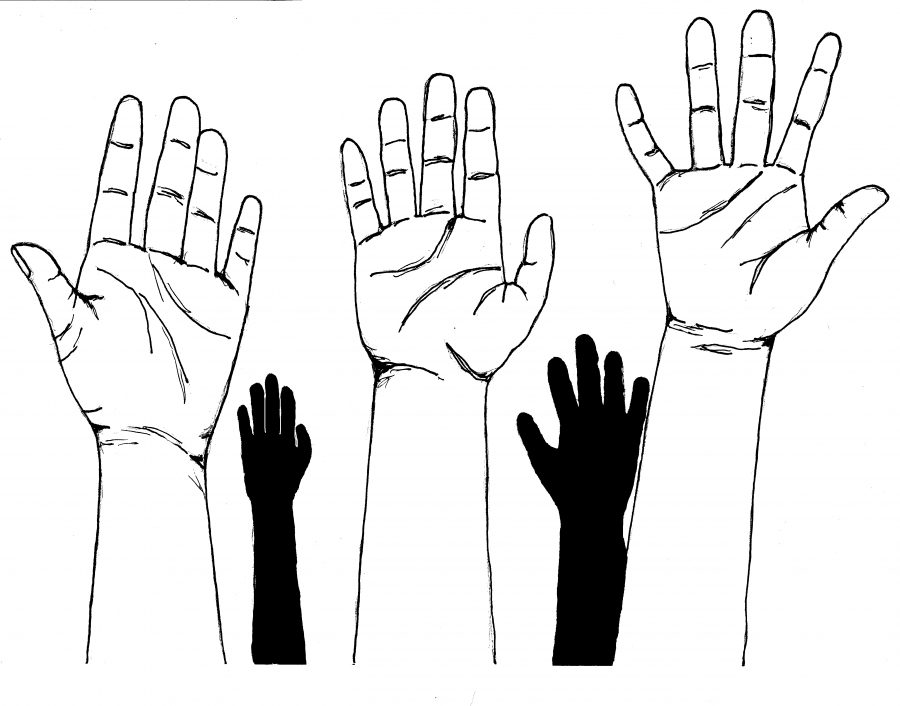

APPartheid

How Garfield’s classrooms exclude students of color.

“Last year I remember we were learning about world religions so we watched a bunch of videos about Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism and Confucianism, and everyone that was interviewed as a historian or academic was white and a male, and when I brought it up to [the teacher] , he just ignored me.”

-Jaya Duckworth, 10th

“No matter what, even if there is an effort made to include you or diversify what we’re learning, since white students make up the majority of the class, it will always be molded for them. Also, in my classes there are people who say things to intentionally hurt people of color, and that is just an uncomfortable situation for me to be in.”

-Naomi Haile, 10th

“I did a group project on self-segregation for which we handed out a survey about why people self-segregated and a lot of the white people took no responsibility and essentially blamed it on chance.”

– Amira Abdel-Fattah, 12th

“[One of my teachers] makes a point to pronounce students of color’s names wrong. Like she either just hasn’t made an effort to learn anyone’s name or she’s trying to be funny, but it’s just not okay.”

-Angelena Tran, 10th

Two years ago, the McGraw-Hill textbook company came under fire for an entry in its 9th grade World Geography book that read, “The Atlantic slave trade between the 1500s and the 1800s brought millions of workers from Africa to the Southern United States to work on agricultural plantations.”

By describing the millions of slaves brought without consent during the Atlantic Slave Trade as “workers,” people claimed the textbook minimizes history, and completely ignores the fact that these people were forced here against their will.

Textbooks and curriculum are painfully lacking in perspective, particularly in Advanced Placement (AP) and Honors classes. When history is almost always written by highly educated white men, the stories we hear in classrooms are unbelievably one sided. AP and Honors classes are undeniably missing diversity, as they almost always have predominantly white and Asian students and teachers.

Although there are certainly teachers who make an effort to diversify their classrooms with additional primary sources from a variety of perspectives and inviting students of color to share their perspectives, these efforts can be outweighed by harmful microaggressions, intentional or not.

Furthermore, when a unit is taught about people of color, it is more often than not about the struggles these people have faced, rather than the achievements they have made and the ways they have positively impacted society. The numerous accomplishments of Japanese-Americans aren’t taught in most history classes, but the Japanese Internment is almost always addressed.

When students of color don’t see themselves reflected in curriculum or receive equal attention from their teachers, it can be difficult for them to succeed. This problem doesn’t only exist at Garfield. A 2016 study by the Stanford Center for Education Policy Analysis reported that Seattle

Public Schools’ Black students test, on average, three and a half grades lower than their white peers. Similarly, the gap between white and Hispanic students is around two and a half grade levels. When compared to the 200 largest public school districts in the country, Seattle’s achievement gap is the fifth largest.

The school district is aware of these issues, and work is being done to correct the problems on a city-wide scale.

“At Seattle Public Schools, our fundamental belief is that every student entrusted to us will attain high academic performance and will achieve academic excellence. While this is a reality for some of our students, it remains a dream deferred for many of our students of color (African-American, Latino, Native American, Pacific Islanders, and Southeast Asian),” explained the school district website. “That is why we are declaring our commitment to eliminating opportunity and achievement gaps and accelerating achievement for each and every one of our students.”

The parents of white students, particularly those on the APP track, have sometimes reacted negatively to these goals. Complaints are often made that their children are not receiving equal attention or resources, when compared to students of color. The implementation of Honors for All at Garfield received a fair amount of pushback from parents of students that were already on the honors track because they feared the program would hold their children back. What these parents fail to realize is that diverse classrooms and a variety of perspectives in curriculum will only make learning more interesting and valuable for every student. We at Garfield owe all students equal opportunities and should continue to work to make sure every student feels included and welcomed in our classes.

“At the beginning of the school year, we were watching this movie about the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, and there were like three Black students in the class. The whole time we were discussing the movie, he would ask all three of us to be a spokesperson for all of the Black people in the United States. It was just really awkward because I can’t speak for the millions of Black people in the country. It was really uncomfortable because [the teacher] really just points at students to be a spokesperson and give the whole history and story of all people, but that’s just not your place to do that so it’s really weird.”

-Hailey Gray, 10th

“In middle school, I was in APP, and there was only one Black student in the class. We had this old white lady as a substitute one day, and the first thing she did when the bell rang was to ask the Black kid if he was in the right room.” -Anonymous

“My [World Lit Class] is all white and it is super uncomfortable when we talk about race.”

-Cecilia Hammond, 10th

“In my Spanish class, which is predominantly white, a lot of students treat the culture we learn about as a joke, which is really uncomfortable.” -Anonymous, 9th

Art by Ana Matsubara