From Another Mother

The Issue of Identity among adopted students.

Adoption, an increasingly available option for people who are unable to conceive, prefer to adopt, or are single, can lead to identity dilemmas among adopted youth. This type of obstacle is especially common among people who are internationally or transracially adopted.

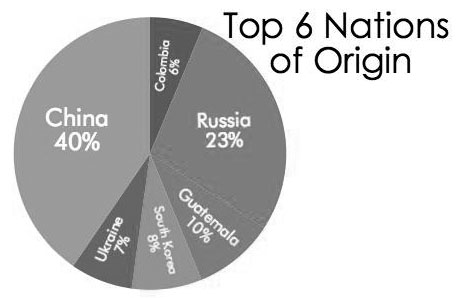

The United States is currently the largest receiving country in the world. South Korea was the first country from which Americans adopted significant numbers of children, beginning in the 1990s. It is still among the leaders in international adoptions, along with, Guatemala, Ukraine, Russia, China, India and Ethiopia. According to the Department of Health and Human services, more than 40% of adoptions are transracial, meaning the child is of a different race or ethnicity from their adopted parents.

Often, adopted people end up feeling a disconnect from their biological relatives and birthplaces.

Freshman Adanech Muno was adopted from Ethiopia at age four. She was raised by a white family in a predominantly white community. Muno has not been back to Ethiopia since her adoption, but she is attempting to stay connected with her culture by learning the language and staying connected with her biological relatives.

“My parents never denied me the opportunity to reach out to my family back in Ethiopia,” said Muno. “I know how to get by with interactions. Like I know how to say hi, hello, what’s up and stuff, but I’m learning [the language] slowly just because I haven’t been around it as much. I haven’t been able to keep up with it.”

For Muno, understanding her identity has been an obstacle. “[My identity] has been a huge issue for me because to Ethiopian people, I wasn’t Ethiopian enough, and to Black Americans, I was too white-washed, and with white people, I was the only black person,” said Muno.

Coming to Garfield has been a transition for Muno.

“I was so relieved when I came to Garfield… I was like ‘oh my god, black people’,” said Muno. “I think that at Garfield I’ve been able to interact with all types of people. I’ve definitely been able to connect more with Ethiopians and my heritage.” Muno’s parents try their hardest to keep her and her siblings connected to their heritage.

“I had a hard time with [my identity] for a while just because I grew up in a white family, but my parents do try really hard to keep us in the Ethiopian community,” said Muno.

While Muno still has a strong connection to her heritage, many adopted people are in an entirely different situation.

China has been the leading country in adoption for the past few decades. This is partially due to the One-Child policy which was introduced in 1979 and lifted in 2015. This social experiment hoped to shrink China’s enormous population. However, Chinese families felt pressured to have a male heir, leading to the

abandonment of thousands of female infants. Almost 90% of adopted Chinese people are female. Adopted Chinese people living in the US often don’t know their original name, because they were re-named by the orphanages, and have no connection to their birth parents.

Aside from issues concerning identity, adopted children wish to know more about their background because of medical reasons. Many adopted people have no way of knowing if their relatives have a history of diseases or disorders, putting them at a higher risk.

Different countries and adoption companies have very strong apprehensions about adopting out to same-sex couples and single parents. Thousands of potential parents are unable to receive children, even though there are over 100,000 foster children eligible for and waiting to be adopted.

Domestic adoptions (adoptions in which the biological parents of the child are both US citizens) have surpassed international adoptions in recent years. Although there is not always the same cultural transition that internationally adopted people undergo, domestically adopted people can experience issues with understanding their identity. An anonymous student has also experienced some similar emotions concerning her identity.

“I often find myself wondering where I come from. I know both my birth parents, but I don’t really know any history about my family,” said the student. “I didn’t know my birth dad until sixth grade, so I was kind of always wondering why he had left me and why he didn’t want to have contact with me.” Although this student has had some challenges understanding their Identity and background, she could not imagine her life playing out any other way.

“It”s really strange to me to think about coming from the parents I live with, like not having two moms and two dads from different families sounds very strange to me,” said the student.